Alison Brackenbury was born in Lincolnshire in 1953, from a long line of domestic servants and skilled farm workers. She won a scholarship to Oxford, where she studied English Literature. In 1977 she moved to Gloucestershire, where she worked in a technical library, then, for 23 years, (in a blue boiler suit!) for her husband’s tiny metal finishing company. Since her retirement in 2012, she has given readings at many festivals and other poetry events.

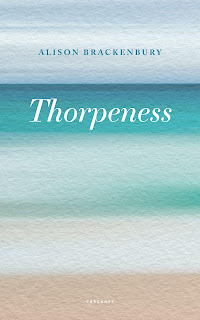

Alison’s work has won an Eric Gregory and a Cholmondeley Award. She has broadcast frequently on Radios 3 and 4, either reading individual poems or narrating poetry programmes which she has scripted. Gallop, her Selected Poems, was published by Carcanet in 2019. She would admit to having spent far too much time on animals (especially horses), and far too little on books, including her own ... Nevertheless, Thorpeness is her tenth poetry collection.

Alison is disgracefully active, as a poet, on the Internet. She posts poems and nature photographs on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. New poems can be read at her website here.

About Thorpeness, by Alison Brackenbury

Thorpeness is the place which Alison Brackenbury intends to reach. On the way, often in the tiniest of poems, she meets birds: the heron rising from a startled suburb, the fieldfares on the stony hills. She sees our planet sailing into darkness. She walks in woods, and thinks that we may survive. Thirty-five years of horse-keeping crumple to the ground with one old pony. But, in a time of fear, she re-discovers love, in a field strewn with blue willow pattern. She recalls the people of her past, with their Christmases and sugar mice.

A treasured black oilskin notebook gives to the poems of Thorpeness (and to an acclaimed Radio 4 feature) the recipes which marked the life of Dot, her tiny, indomitable Lincolnshire grandmother: ‘Vinegar Cake,’ from war-time, ‘Oat scones’ made for children, and the jam-veined, steamed richness of ‘Flamberries Pudding.’ Brackenbury never reaches Thorpeness. But her swallows fly beyond it.

Below, you can read two poems from the collection.

From Thorpeness

We made them for the village fete.

So I was sent up to the gate

to ‘Grammar,’ if they could have bought

a crested cap, soft shoes for sport.

The one girl he had waited for

ran to an airman in the War.

A courteous, clever man, all said.

In June heat, at a long lane’s end

I stepped beneath the roses’ cloud.

I saw him bend to stakes, head bowed

for farmhand’s collar, or the Queen,

webbed, spread like hands, its tiny veins

crisp as dead leaf, all green, so green.

a lockdown walk

Town’s edge. A lane. A bridge. A field

marched by the battered stumps of maize,

lit by hills, broad as the moon.

The cracks in April clay will yield

rich oyster shells to feed poor days;

pipes; pigs’ skulls; best, we find soon,

slipped from quick hands, a child’s, a maid’s,

to floor. Were harsh words spoken?

I brush a latticed rim while you

scoop one white scrap whose two blue birds,

smudged lovers, soar unbroken.

No comments:

Post a Comment