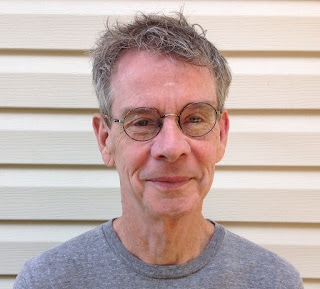

Rory Waterman was born in Belfast in 1981, and grew up mainly in Lincolnshire. His fourth full-length collection, Come Here to This Gate, has just been published by Carcanet Press. His other collections, all published by Carcanet, are: Tonight the Summer’s Over (2013), which was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation and was shortlisted for a Seamus Heaney Award; Sarajevo Roses (2017), which was shortlisted for the Ledbury Forte Prize for Second Collections; and Sweet Nothings (2020). He is also regularly a critic for the TLS, PN Review and other publications, and has published several books on modern and contemporary poetry. He co-edits New Walk Editions with Nick Everett at the University of Leicester. He has a BA and PhD from the University of Leicester. Since 2012, he has worked at Nottingham Trent University, where he is Associate Professor of Modern and Contemporary Literature and leads the MA in Creative Writing. He lives in Nottingham. His website is here.

About Come Here to This Gate

Come Here to This Gate, Rory Waterman's fourth collection, is his most candid and unexpected, personal, brash, hilarious, and wide-ranging. The book is in three parts, the first a sequence about the last year of the life of his father, the poet Andrew Waterman, against a backdrop of recrimination, love and alcoholic dementia: "your silences were trains departing." The second consists of poems that open various gates, or are forcibly restrained behind them, from the literal North and South Korean border to the borders between friends, and those imposed by photographs, memories, and paths taken and not taken. The third opens on the poet's rural home county of Lincolnshire. He rewrites several folk tales into galloping, sometimes rambunctious ballads for the 2020s: what happens when imps, ghosts, and a boggart who looks like a "doll left behind at Chernobyl" must reckon with the modern world and the people who lumber through it.

You can read more about Come Here to This Gate on the publisher's website here. You can read a review of the book on Everybody's Reviewing here. Below, you can read two poems from the collection.

From Come here to This Gate, by Rory Waterman

Home

T-shirt weather today: a bumble bee bumps

the window, and the door of the visiting room

yawns and nudges a pot. We could go out,

sniff freedom over the fence. You’d rather not.

‘You’ve come to take me home?’ No, Dad. I’ve come

to bring it to you, blind on your piss-proof seat

on wheels, most of you a line of little knots

beneath a blanket. Stop-gap Clov to your Hamm –

you’d get that, and it wouldn’t help – I ask

someone to bring your sippy cup, some biscuits,

and you chew them in the back of your open mouth

in quiet, ‘thinking,’ too afraid to talk.

So I watch the ridge of your forehead, feel my own –

for impulse, or connection, which doesn’t come

until a nurse does, panting, to the door,

to tell us darlings we have five minutes more.

(first published in the Times Literary Supplement)

ICN to LHR

‘Keep the reunified Korea in your heart’

an old man had said, palming his chest. And

okay, I do. And there it stays, doing nothing

as flight KE 907 to London lifts

from a (re)claimed island, over (re)claimed islands

stacked with containers: a concreted sarcophagus,

the memorial to Operation Chromite,

which has no other memorial. A child beside me

pulls down her mask, is chastened, frumps.

‘We’re progress,’ he had added. See it down there,

a phosphoresced capital washing round its hills,

a land of neon chaebols and kimchi jars

where new friends complete the circuits

of their lives for Samsung, Lotte, Hyundai,

as I complete this circuit for Hanjin.

See the sea ooze the yellow they don’t call it

here – there – with silt from China, as we skirt

North Korean airspace. This land is your land

I hum before noticing. Far towns are like colonies

of barnacles; dark fishing vessels ply

what looks turbid. And when we start to cross

the safety of China, from where this – that –

is ordained, a city (Shenyang?) shifts,

a molten web in new night. Now there will be

nothing but black, the dark familiar nowhere,

and then the grind of lowering, the misted plots

of ruined nametagged earth around our lives.

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)